The following slide presentation outlines our three outcomes for collaboration, the specific resources/platforms we chose to focus on, our rationale, an overview or general evaluation of resources, a critical evaluation of each of the chosen resources, and a conclusion. Please see the table of contents for specific topics related to evaluation.

Decolonization Processes In Education: EDCI-532 Assignment #2

Introduction:

“Attempts at the so-called inclusion of Aboriginal perspectives have usually meant that an anachronistic study of Aboriginal people is offered as a possibility in classrooms only if there is time and people are still interested” (Donald, 2009, p. 23). As a social studies teacher, Donald’s quote resonates with me; it highlights the necessity of decolonizing curriculum. So often, curricular developers and educators have placed Indigenous content on the periphery of teaching importance, rather than weaving it throughout and providing it with the same attention as other historical events. Whether it is lack of knowledge or resistance on behalf of scholars, educators, teacher training programs or curricular developers at the provincial levels, I believe, we all have a role to play in providing and strengthening “the representation and centrality of Indigenous peoples” (Gibson, L., & Case, R. 2019, p. 255), within Canadian history courses, curriculum and education as a whole. To make changes and move forward education, specifically a more inclusive curriculum, it is essential to understand where we came from in terms of early pedagogy and practices.

My Connection to Decolonization of Curriculum as a Social Studies Teacher:

Traditionally, Canadian history curriculum and teaching practices have been developed and taught, respectively, upon a Euro-centric or ethnocentric perspective. Consequently, this frame of reference has left Canada’s Indigenous population marginalized, as their contributions and tragic losses, which have played significant roles in the shaping and development of Canada, have not received the recognition that is rightfully deserved. In 2015 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its Calls to Action, “to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation” (TRC, 2015, p. 1). This motion calls upon various levels of government to make changes in a variety of areas, including education. Specific reforms include “the development of curriculum and integration of knowledge on Indigenous historical and contemporary issues in primary and secondary education” (Morcom, L., & Freeman, K., 2018, p. 811) and “the training of teachers to advance awareness of the history and legacy of residential schools, [in addition to] tools for building student…intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect” (p. 811). As a social studies educator, I am grateful for the changes that our provincial government has made regarding implementing more Indigenous content throughout the social studies curriculum. For example, one of the curriculum competencies facilitates learners in making ethical judgements through the examination of actions that existed in the past and present in reference to the lives of Canada’s First Nations population (“Social studies 10 | Building student success,” 2018).

Photo By Maher-El-Aridi on Unsplash

Furthermore, the development of the Indigenous Knowledge and Perspectives in K-12 Curriculum has served as an invaluable guide with which I am becoming more confident in using to immerse my learners in a wealth of Indigenous content. In addition to British Columbia’s welcomed changes, I also believe it is my responsibility, to look within my community and seek further education. Both my students and I benefit from the rich oral narratives that local First Nations knowledge keepers and elders hold. These individuals provide first-hand accounts of their own experiences that are not found in textbooks. My connection to the significance of immersing both myself and my learners in Indigenous content, to truly understand, acknowledge and honour the truth around the development of our country, is supported by various researchers.

Article Examination on Decolonization of Curriculum:

Articles by Gibson and Case (2019) and Morcom and Freeman (2018) highlight the necessity for both curriculum and teacher training, respectively, to be developed in such a way as to break down barriers that traditionally have kept Indigenous perspectives and content on the periphery of education. Gibson and Case (2019) identify that although some scholars and curricular developers disagree with changing Canadian historical curriculum as it “rejects the discipline of history and historical thinking” (p. 251), they propose that simple changes can be implemented without “radical epistemological restructuring” (p. 251), thus meeting the TRC reforms. The first change, noted in Gibson and Case (2019), involves bringing indigenous content away from the sidelines and bringing it to the forefront. The authors suggest this can be done through the engagement with local Elders, Indigenous literature, primary sources and other resources produced by Indigenous members. The goal is to “go beyond sprinkling…Indigenous historical content into a predominantly Euro-Canadian curriculum” (p. 254), rather immersing in it. Second, teach learners the skills to become in-depth thinkers, thereby challenging them to “think historically by interpreting historical evidence” (p. 254), rather than simply accepting the norm or what has been acceptable in the past. Gibson and Case (2019) argue that this skill is important for students to recognize discriminatory views and perspectives. Third, provincial and territorial curriculum developers should create more courses dedicated to focussing on “Indigenous historical and contemporary world views” (p. 254-255). It should be noted that the authors recognized that there are several regions in Canada, such as British Columbia, that have made some changes, similar to their recommendations, to meet the TRC recommendations.

Morcom and Freeman (2018), stress the significance of valuing local First Nations culture and encourage teacher candidates to become involved with the teachings of local First Nations’ knowledge keepers and elders. The co-authors, both educators within the Department of Education’s Aboriginal Teacher Education Program (ATEP) at Queen’s University, use the Anishinaabe First Nations’ “philosophy, worldview, culture and spirituality…as a source of information and guidance in…[their]teaching” (Morcom, L., & Freeman, K., 2018, p. 814). Specifically, the educators connect their methodologies and pedagogies to the traditional “Seven Grandfather Teachings, [including] honesty, humility, respect, bravery, wisdom, truth and love” (p. 815), and the medicine wheel, which encompasses “the for directions, sky, earth, [and] center” (p. 815). Morcom and Freeman (2018), argue that their teaching methods enable teacher candidates the opportunity to develop a deep understanding, knowledge and respect for the Indigenous culture, and the significance of including it in both curriculum and teaching methods. Furthermore, Morcom and Freeman (2018) argue that following this inclusive style of teaching meets the reconciliation requirements set forth by the TRC, and more importantly, facilitates in the development of future teachers recognizing and respecting the need to build a more inclusive and just society (p. 829).

The above-mentioned authors clearly provide welcome guidance as to how educators can work on improving their knowledge of Indigenous content with which to bring to the classroom. Their perspectives and methods are informative, and they provide current teachers and teacher candidates with the opportunity to constructively think about how to stop the marginalization of Indigenous content that has existed in society, or education, for far too long.

Conclusion:

The traditional methods of teaching Canadian history followed a very ethnocentric perspective, with the exemption and romanticism of Indigenous content. The TRC’s Calls to Action around education has identified the significance of decolonizing curriculum and supporting educators in developing their knowledge of Indigenous culture. I believe, to have an honest, just and inclusive education system, it is essential as educators to discuss, learn, and question past wrongs alongside our learners, to break down the barriers that colonial views had originally established in early curriculum.

References:

Donald, D. T. (2009). The curricular problem of Indigenousness: Colonial frontier logics, teacher resistances, and the acknowledgment of ethical space. Beyond ‘Presentism’, 23-41. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789460910012_004

Education for reconciliation. (2019, September 5). Relations Couronne-Autochtones et Affaires du Nord Canada / Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada – Canada.ca. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1524504501233/1557513602139

Gibson, L., & Case, R. (2019). Reshaping Canadian History Education in Support of Reconciliation. Canadian Journal of Education, 42(1), 251-284. https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/3591

Morcom, L., & Freeman, K. (2018). Building Non-Indigenous Allies in Education. Canadian Journal of Education, 41(3), 808-833. https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/3344

Social studies 10 | Building student success. (2018). Building Student Success – BC’s New Curriculum. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/10/

(2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). https://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

My Personal and Professional Experiences With Accessibility: EDCI-565 BLOG #2

Picture By John Hoang on Unsplash

Introduction:

In EDCI-565 we had the opportunity to listen to Kim Ashbourne present on the significance of accessibility of education to all learners. Her presentation pin-pointed various resources that outline the human rights all individuals have in terms of accessing education, in addition to providing educators with further information in order to assist them in gaining ideas in which to help learners with diverse needs. Two specific websites of interest that were shared, included World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) which focuses on “strategies, standards, resources to make the Web accessible to people with disabilities” (W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), n.d.), and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) which provides “a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn”(“CAST: About universal design for learning,” 2019). The area of accessibility to learning connects with me both personally and professionally, in terms of my own experience with a hearing impairment, and as an educator working to support my students during the interruption of regular classes because of COVID-19.

Personal Connection:

On a personal level, as previously mentioned, I have a hearing impairment caused by a viral ear infection that damaged my right ear and resulted in between 60% – 70% hearing loss. After multiple scans and cochlear injections, the end result was acquiring a hearing aid. I am grateful to have the hearing device, however, it is not the same as having a full range of natural hearing ability. Sound is different and does take time for your brain (and in my case patience as well) to adapt. Background noise and the speed of a speaker’s speech can impede clarity and understanding; and furthermore, the direction of sound can be difficult to pinpoint in terms of its origin (coming from left or right). Consequently, I have had to make adaptations to assist myself where my hearing is concerned. The changes and at times frustrations, all be them mild, have definitely opened my eyes and increased my understanding of the necessity of accessibility for all learners in terms of any challenges they endure. More specifically, it has forced me to pay closer attention, professionally, to various ways or types of technology or teaching methods I can use so as to assist learners reach their goals. Some examples of technology that have assisted students either directly in my classes or within our school include, but are not limited too, the use of individual laptops or tablets in lieu of physically writing down notes or completing assignments, digital translators for international students that do not have a strong background in English, speech to text programs for those with challenged motor skills, text to reading programs for those learners with reading difficulties, and videos/dvds for visual learners. Having access to various technologies are essential to support learners with their various modes of learning and diverse needs, as it provides a gateway to equity in their learning, as much as my hearing aid supports me in my endeavours.

Educational Challenges to Accessibility During Covid-19:

The onset of COVID-19 has been a further eye-opening and challenging experience in terms of accessibility to online education and support. As an educator, it has been difficult to provide online lessons, assignments, activities and support as most of my learners rely on the digital tools available to them at the school, and have little to no access to technology at home, for various reasons. Resulting from these digital challenges, most of my learners and/or guardians requested hard copies or packages that could be picked up and dropped off on a routine basis. Providing physical packages were better than nothing. I was also able to follow up with support and discussions via texting, emailing and phone calls. However, not having the same technical support at home, as is available and/or relied upon by some at school, did limit some learners’ access to equity in their education.

Conclusion:

In the coming weeks, as our provincial government releases plans for the next school year, I hope there are considerations about opportunities for access to those students living in remote locations, in families that are socio-economically challenged, or living with learning challenges to be able to access the digital supports they need to enhance their educational experiences and equity in their learning.

Curriculum: The Tree Roots Necessary to Build and Support Learning Assignment #1 EDCI-532

My Curricular Metaphor:

Curriculum is the root system of a tree. It enables a strong trunk, branches and eventually buds, leaves and or needles to grow and develop. The roots (like curriculum) are essential to the life, growth and development of the tree over the course of its lifetime, and it fulfills many significant responsibilities. The root system establishes a solid foundation, provides the nourishment needed to feed the tree, extends support and strength while at the same time allowing for flexibility. This is exemplified when a tree sways in the wind or bends to grow toward the sun, encourages the growth of new root shoots to facilitate in the growing process, and lastly they adjust to environmental changes to withhold its structure and integrity. Curriculum, like the root system, also has many responsibilities to fulfill. It provides learners with necessary structures to use as a base upon which to build and develop further knowledge and understanding of the concepts being taught, contributes to the nourishment of knowledge, self-confidence, rigour and expansion of one’s skill set, promotes new learning opportunities, and accommodates for various learning styles and interests. Without a sturdy, grounded root system, or curriculum, it is difficult to support learner growth and advancement.

My Teaching Context:

At Fort St. James Secondary School my teaching content area further reminds me of the intertwined nature of a tree’s root system, as I teach various courses. Consequently, I seek guidance and structure from various arenas that support Social Studies 10, Career Life Education 10, and Career Life Connections 12. The specific curriculum I rely on, as set forth by the BC Ministry of Education provides structure while at the same time is open for individualization. Social Studies 10 curriculum I follow, includes the BC Social Studies 10 Curriculum, and Indigenous Knowledge and Perspectives: Social Studies K-12 Curriculum. Other areas I seek support from include Elders or Local Knowledge Holders (from the Nak’azdli Whut’en First Nation), First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC) and CIVIX Canada. For the Careers context, I use the BC Career Life-Education 10 Curriculum, and BC Career Life Connections 12 Curriculum. To further support student learning and engagement I also use MyBlueprint, Career Compass, Education Planner BC, and Student Work-Safe. I believe the ministerial curriculum documents provide a strong framework with which I can build upon, using the additional aforementioned resources.

Egan VS. Blade: As I See Them

Egan’s and Blade’s viewpoints on what best constitutes curriculum could be seen as divergent. Egan, for example, argues from a constructivist standpoint supporting the notion that the what or the content needing to be taught is the most significant aspect that the curriculum and should be focussed on and built upon. In addition, he does not support how viewpoints or questions that focus on how the learner will learn best or how individual learning processes should be the building blocks of a curriculum. This notion is further supported by his statement that “curriculum is the study of any and all educational phenomena, [and] may draw on…external discipline[s] for methodological help, but the methodology doesn’t determine the inquiry (Egan,1978, p.16). Furthermore, Egan suggests that “what the curriculum should contain requires a sense of what the contents are for” (p.14), thus suggesting that specific curricular content would have taken into account the individual knowledge and skills that will be learned, rather than how they will be learned. Lastly, Egan suggested that if curricular content focused on how individuals each learn best, there will be a lag in the amount of knowledge gained, moreover, it does not provide a sound framework of content with which one can build upon, and instead, it leads to unclarity (p.14).

Contrary to Egan’s article, Blade identified the individual’s learning processes and their voice as an integral part of curriculum development. Blade, who took a more deconstructivist approach, recognized that being trapped within the confines of a content-driven curriculum, actually “exclude[d] and limit[ed]…possibilities” (Blade,1995, p.129). Furthermore, he identified that those who traditionally held positions of power, within curriculum development, rarely regarded the individuals that worked directly with it and/or affected by it. His statement identified that in these situations the “truly critical voices [of learners and educators] in the discourse were…seen as antagonists by the major voices” (Blade, p.147), thereby acknowledging that former processes resulted in a loss of pertinent information that could have been useful in developing curriculum.

I feel Egan’s and Blade’s viewpoints, regarding what curriculum should be focussed on, are equally significant. Although I sway toward Egan’s argument for the necessity of a strong and purposeful curriculum with clear and defined content from which to build upon, I am not as stringent. I recognize the need for individuality in learning. I prefer to follow a concrete curriculum and use it as scaffolding for future learning to build upon. However, I also integrate learner individuality to provide learners with the opportunity to demonstrate their learning process through individual measures and questioning. By following this process I believe it enables one to showcase their strengths while at the same time providing equity.

References

Bishop/unsplash.com/photos/EwKXn5CapA4

Blades, D. (1997) Procedures of Power in a Curriculum Discourse: Conversations from Home. JCT, 11(4), 125-155.

Egan, K. (2003) What is Curriculum? JCACS, 1(1), 9-16.

Designing Curricular Activities: EDCI – 572 Blog #4 March 28, 2020

“May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds.” Edward Abbey

“May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds.” Edward Abbey

INTRODUCTION:

The above quote resonates with me as I reflect on the professional challenges that lay ahead in terms of providing educational opportunities to my current learners. I feel as though I am on an unknown trail. I am not sure which direction I am going, what obstacles and their difficulty lay ahead, what equipment may be necessary to assist in overcoming hurdles, and where the trail will finally end. Although I may feel intimidated by the unknown challenges, I recognize that this journey will enable me to develop new strengths and skills while working towards the ultimate goal of facilitating in my students’ learning successes (metaphorically reaching the summit).

IDENTIFYING LEARNER EDUCATION ACCESSIBILITY:

In terms of how, exactly, I will be providing educational opportunities and support to students, thereby facilitating their learning, is unknown at this time. Suffice to say, that is my “wicked problem”(Buchanan, 1992, p. 14). Given the demographics of our school community, there must be more than one design plan or option made available to honour accessibility for all learners, while at the same time supporting their critical thinking skills and learning growth overall. Designs chosen to assist learners, according to Richard Buchanan, must “…integrate knowledge in new ways, suited to specific circumstances and needs” (Buchanan, 1992, p. 19). Therefore, when thinking of my classes, I have identified three groups of learners I must consider, including when designing course material.

Consequently, it is essential to provide options to learners that will support them in their learning endeavours, based on the learning provisions they have available to them, outside of the regular classroom setting.

For those students (GROUP A) with computer and internet access, there are a variety of ways they can demonstrate their learning, critical thinking skills and reflecting, including but not limited to creating My Blueprint portfolios, Prezi, PowerPoint, and Adobe Spark. Using these digital literacies will enable students to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding in a variety of formats that involve critical thinking skills. Furthermore, the skills used to create and complete assignments digitally, connect to the learning outcomes listed in the BC Digital Literacies Framework. For example the learner:

-

-

- Locates, organizes, analyzes, evaluates, synthesizes and ethically uses information from a variety of sources and media. (Gr. 10-12)

-

-

-

- Integrates, compares and puts together different types of information related to multimodal content. (Gr. 10-12)

-

-

-

- Creates complex models and simulations of the real world using digital information. (Gr. 10-12)

-

Lastly, for those learners with computer/internet access, it will be easy for me to provide quick feedback and online assistance through email.

For students without internet access, (GROUP B) it will be more challenging to support them in their learning, however not impossible. Although these learners may be more restricted to traditional methods, which involves picking up and dropping off a paper-based learning package from the school, they can still complete assignments that support both their learning and the development of their critical thinking skills. For example, learners can create posters, written personal responses or reflections, timelines, flow-charts, diaries, 3-D creations and pamphlets to demonstrate specific concepts. Unfortunately, these learners will not have access to rapid feedback like those in the previously mentioned group. Communication may exist in the form of a phone call to them or if allowed, a brief meeting/tutorial at school.

The third group of learners (GROUP C), will follow a similar in learning design to the second group (GROUP B), where they would also complete a paper-based learning package; however, the difference being that they would not come to the school to pick it up or drop it off. This group of learners includes those that are regularly bussed in and out on a daily basis, and may not have the support at home to provide transportation to come into the school to pick up and/or drop off work. As busses will likely not be running, there is a chance that educational packages will have to be taken from our school, by a designated individual, to a particular location where families can come, and pick up and/or drop off materials on specific dates, such as once a week.

MY CONNECTION TO BUCHANAN’S ARTICLE:

Upon reading Buchanan’s article, I was able to connect my three groups of learners, based on their learning accessibility, to the four levels of design which included: Symbolic and Visual Communication, Material Objects, Activities and Organized Services, and Complex Systems & Environments for Living, Working, Playing and Learning. (Buchanan, p. 9 & 10). Although assignments and delivery will vary in the design format between each of my learner groups, the end goal, being that of learner success in understanding and demonstrating knowledge around specific content, will remain the same.

Connection Between the Four Levels of Design and My Learning Groups

| 4 LEVELS OF DESIGN | GROUP A | GROUP B | GROUP C |

| SYMBOLIC & VISUAL COMMUNICATION | Education completed via online activities with online communication with the teacher. | Paper-based packages will be created for students with teacher-written instruction. | Paper-based packages will be created for students with teacher-written instruction. |

| MATERIAL OBJECTS | Textbook, computer and internet access. | Textbook and teacher created work packages. | Textbook and teacher created work packages. |

| ACTIVITIES & ORGANIZED SERVICES | Prezi, PowerPoint, MyBlueprint, Google slides, Google share docs, & Photoshop.

Feedback via email and or phone. Students are responsible for electronically submitting assignments by the assigned date. *Assignments in this group also connect to the BC Digital Framework. |

Complete various types of critical thinking assignments that can be supported through a variety of methods such as written/built projects.

Students are responsible for picking up and dropping off packages by assigned due dates Communication via phone. |

Complete various types of critical thinking assignments that can be supported through a variety of methods such as written/built projects.

Packages will be delivered to a specific location for drop off/pick up. Students are responsible for making sure assignments are completed by the assigned date. |

| COMPLEX SYSTEMS & ENVIRONMENTS | Continue to develop and provide greater only support to access subject material easily | Continue to create work packages and provide easy access at school for students to drop off/pick up if they do not have internet access at home. | Continue to create work packages and work with an outside agency, such as an Education Director to deliver/pick up packages directly to/from students without the internet or accessibility to come to school to pick up packages themselves. |

CONCLUSION:

Regardless of the method of educational support, my learners will be receiving, I recognize it will not be seamless. It will be a huge accomplishment for all. Furthermore, it will be essential for me to consider individual challenges with technology, including limited usage or time constraints, as other family members may need to access the computer for their courses as well. For all learners, it is essential for me to remember that they will be taking on challenges from many courses at once, and working in diverse learning environments.

Clearly, navigating this new winding trail of education design and delivery will be a challenge. However, it is a challenge I believe is worth taking on, and one that can be met.

By: Deirdre Houghton March 28, 2020

References

101 inspirational mountain quotes about epic journeys. (2020, February 3). The Broke Backpacker. https://www.thebrokebackpacker.com/best-mountain-quotes/

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (1992). MIT – Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://web.mit.edu/jrankin/www/engin_as_lib_art/Design_thinking

Online Learning: At An Impasse EDCI-572 Blog Post #3

Introduction:

(Photo on Unsplash by Ben Owen).

After having time to reflect on this past week’s sudden and unprecedented changes to the education system, specifically the indefinite closure of schools, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I am having a difficult time grappling the challenges that lay ahead. I am constantly wondering how this situation may be an impasse in halting one’s learning journey. Indeed this anomalous situation is perplexing, both personally and professionally.

Admittingly, I completely understand the reasoning and necessity behind the swift closures and respect the installation measures put in place for the safety of us all. This experience, when compared with my previous hiking/trail running metaphors, is much like enjoying scenic trails, then, suddenly, around the next corner, unbeknownst, is a mother black bear and her cubs. Clearly this situation, much like the school closures, stops one in their tracks. It is these unforeseen events that force us, as educators, to accept challenges, make changes successfully work through the hurdles and support our learners.

Personal Struggle:

In regards to my personal struggle around school closures, although frustrating, they are very insignificant compared to the struggles that others around the world and indeed our country are enduring at this time. The closures, however, remind me of the frustrations that some learners may have with not having a connection to the internet to support their own learning needs.

Last week, our little cohort of three in Fort St. James spent a great deal of time collaborating and completing tasks associated with our EDCI-572 project. We gratefully took advantage of many of the digital tools we have access to in our school. Then, suddenly, we were notified that all staff, district-wide, would be permanently locked out of the school over the course of spring break so decontaminating processes could be completed. This notice quickly put us into overdrive to complete as much work as possible, in a short period of time. No longer would we be able to meet as a group on our regular Tuesday nights for our online class or meet at designated times at school to discuss our progress and what our next steps would be. In short, our spring break masters’ meeting schedule was stopped, and our present learning journey is forced to take a different path. Initially, my panic button or alarm sounded as I started to think about the internet access I have at home, which is spotty at best (hence the need to work at school). Upon quick discussions and multiple texts, we have come up with a few plans, not limited to sitting in the school parking lot with a laptop, to access the internet. Although these challenges have forced us to make quick changes so that our learning journey can continue, it has forced me to think (and worry), professionally, about the learning journey that our learners will be heading out on and the challenges they may face.

Professional Struggle:

Professionally, like other educators at this time, I am constantly asking myself questions. Where do we go from here? Now What? Sure we can make up or provide access to online assignments for students, but what about those learners that have a poor internet connection at home, thus leading to growing learner frustration and overall shut down. Then there are also the learners who have neither a computer at home, never mind internet access, and they also do not have parental support for their learning. These learners are the ones that depend on the school community for their learning accessibility and support. I am cognizant of the fact that many of our students live in remote or outline areas, thus bussed into school daily; I wonder if their lack of accessibility to online learning will facilitate in a “shut-down” of sorts in their desire to continue to learn. Have they in their minds checked out and consider school done for the year? Will they be able to make changes that will enable them to meet some challenges in continuing their learning journey?

Conclusion:

Conclusion:

(Photo on Unsplash by Nikita Kachanovsky)

In spite of the fact that there are many online courses and digital supports available to support one’s learning, this unprecedented world situation has made me realize just how fragile online learning connections can be for some learners, especially outside of the school environment. I recognize there is not an easy answer to this situation for any educator. This current impasse will involve various creative and innovative strategies to meet and support the needs of our diverse learners to enable them to continue with their learning journey.

By Deirdre Houghton, March 22, 2020

Guiding Students Along the Mountain Path of Digital Literacy – EDCI #572 Blog 2 (Assignment 1A To Be Marked)

Photo by Heidi Finn on Unsplash

Introduction:

As I ascend the mountain, of digital learning, I am reminded of the plethora of possibilities that digital literacies can provide learners to facilitate and enhance their learning experiences, both now and in their future. Gone are the days where one simply learned skills through a textbook, pencil and paper. Today it is essential for learners to be competent in their digital skills, being aware of their digital footprint, communicate and problem solve using a variety of digital platforms. Digital literacies enable learners to become increasingly creative, innovative and empowered in their own learning. As an educator, I am keenly aware of the necessity of learners to have strong digital literacy skills that can support them successfully in the 21st century. I also recognize that as demands and education pedagogy changes, I too must work on taking further steps, no matter how challenging the trail may be, to continue developing my own digital learning skills to support my learners in their learning processes.

The What, When, and Why of BC’s Digital Literacy Framework:

Tim Winklemans, a member of BC’s Ministry of Education, recently presented BC’s Digital Literacy Framework, to our EDCI- 572 class, which was created in 2015, for the purpose of providing educators with “ an overview of the digital literacy skills and strategies.” scarfedigitalsandbox.teach.educ.ubc.ca The skills highlighted in the document were to serve as a guide for BC educators to follow and integrate into the K-12 curriculum, thereby facilitating “the types of knowledge and skills that learners need in order to be successful in today’s technological world.”scarfedigital sandbox.teach.educ.ubc.ca. The provincial government at the time created a campaign that focussed on making learners’ technology skills highly developed and ready for the digital demands in both post-secondary and the working world. The document itself was designed from basic digital knowledge, as set forth by the National Education Technology Standards for learners, now known by the name International Society of Technology in Education or ISTE. The Ministry’s document describes digital literacy as the “interest, attitude and ability of individuals to use the digital technology tools appropriately.” www2.gov.bc.ca Furthermore, it identifies that digital literacy “takes learning beyond standard tests and enables learning that embraces digital spaces, content… resources and emphasizes that the process of learning is as important as the end product.” www2.gov.bc.ca As an educator, I concur with this last statement. Much like my mountain climbing metaphor, it is the invaluable experiences between the base and the summit, that lead you to your final destination.

The Ministry’s Digital Literacy Framework focuses on six categories and provides each category with respective learning outcomes, to be implemented within the BC K-12 curriculum. The specific areas of focus include Research Information Literacy; Critical Thinking, Problem Solving and Decision Making; Creativity and Innovation; Digital Citizenship; Communication and Collaboration; and Technology operations and Concepts. Although the document is detailed and provides clear learning outcomes, there were some areas of downfall, that as an educator, I noticed. Five specific areas that stood out to me, include 1) not all grades were listed in the sub-topics, in fact, some were left out, 2) there were no connections to any pre-Kindergarten education (or early childhood education) or the roles those educators could or already do support, 3) there was no specific connection to First Nations Curriculum or distinction around cultural traditions that may have not been ordinarily associated with technology, 4) there was no discussion or information given with respect to supporting the digital learning development of learners with special needs, and lastly, 5) there was no discussion around the fact that not every educator and learner has equal access and or support to technology learning tools. Furthermore, I thought that the physical layout could have been improved upon, by categorizing topic headings and outcomes by grade level, in addition to including exemplars to make the document more streamlined and user-friendly. Although the document does provide a wide range of skills, I do think the missing information could have been addressed, thereby making the document more encompassing, comprehensive and inclusive.

My Connection to BC’s Literacy Framework:

In spite of some of the areas I felt that the framework was lacking, it pushed me to think of how I could connect to it professionally and how I could use it to develop my own skills to enhance my teaching practices. More specifically, I concentrated on how it could sync with the expectations within my final master’s project, which I will be completing with my colleagues Andrew Vogelsang and Gary Soles. The focus of our project includes the examination of cross-curricular inquiry within a co-teaching environment and the incorporation of technology, to increase student motivation. Upon brainstorming with my partners, we co-created the chart below highlighting the connections we made with the BC Digital Learning Framework. We included the six categories and their corresponding grade-specific learning outcomes and added the activities learners will be completing to master the learning outcomes.

Upon completion of our chart, we can clearly deduce that our project meets the digital requirements as set forth by the BC Ministry of Education in their Digital Literacy Framework documentation. Furthermore, it acts as a guide that can be used to encourage the implementation of various digital skills and technology to enhance learning in general.

| BC Digital Literacy Framework | Learning Outcome | Student Activity |

| Research and Information Literacy |

|

|

| Critical Thinking, Problem Solving, and Decision Making |

|

|

| Creativity and Innovation |

|

|

| Digital Citizenship |

|

|

| Communication and Collaboration |

|

|

| Technology Operations and Concepts |

|

|

Chart Co-Created by Deirdre Houghton, Gary Soles and Andrew Vogelsang following the BC Digital Literacy Framework as our guideline.

Conclusion:

As an educator, I am excited to see the growth of my learners being able to learn new skills that will be connecting and crossing over into three very diverse course areas, including Social Studies -10, Visual Arts and Computer Technology – 10, and Carpentry 10. The digital literacy skills that I will be developing throughout my course work and project, and in turn, bringing to my classroom, will hopefully encourage my learners to continue to develop their own skills, and further empowerment for them to use their new knowledge and carry it forward in their learning journies.

The video below is a brief introduction and explanation of the Truth and Reconciliation wall art project that our students will be creating in our cross-curricular, co-teaching environment that will be employing a variety of digital literacy skills.

References

BC Ministry of Education. (2015). Digital Literacy Framework. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/kindergarten-to-grade-12/teach/teaching-tools/digital-literacy-framework.pdf

ISTE Standards. (n.d.). ISTE. https://www.iste.org/standards

The UBC Digital Literacy Framework. (n.d.). The BC Digital Literacy Framework. Scarfe Digital Sandbox. https://scarfedigitalsandbox.teach.educ.ubc.ca/the-bc-digital-literacy-framework/

By Deirdre Houghton

Module #5 EDCI – 569: The Rarely Seen Side of Technology

Photo by Alexandru-Bogdan Ghita on Unsplash

INTRODUCTION

When considering the digital world today, so often there is a focus on access, privacy, online behaviour, types of social media platforms, and the newest and best technology, including tablets, laptops and mobile phones, and what new aspects they can provide. Rarely, however, do we stop and think, or discuss the human and natural resource factors that have been used, and in many cases abused, to create the technology we enjoy or depend on today. After reading Jeremy Knox’s article, which focussed on “three critical perspectives on the digital, with implications for educational research and practice,” (2019, p. 357) one perspective that resonated with me was his discussion on the exploration of the “digital as ‘material’ and . . . [the] issues of labour and the exploitation of natural resources required to produce digital technologies.” (p. 357) This particular perspective forced me to stop, think, and research more around the human and environmental impacts that occur because of our consumption and usage of technological devices.

WHAT:

When we enter shiny and glitzy technology or electronic stores, rarely, if ever, do we consider the origin of the materials or human labour used to produce technology devices. Mark Dummett, a human rights researcher for Amnesty International, comments on our lack of recognition, regarding this matter, with his statement “the…shop displays and marketing of the state of the art technologies, are a stark contrast to the children carrying bags of rocks and minerals in narrow man-made tunnels risking permanent lung damage” (Wakefield, 2016). As a humanities educator and user of digital technology, I believe the injustices presented in Knox’s article and Dummett’s quote are important to consider, discuss and reflect upon, with students, in terms of identifying the inhumane labour practices and environmental abuses that occur among many companies tied into the creation of our beloved tech devices.

When working with learners, and examining the origins of technology devices, facts to consider include whether or not companies have used ethically sourced raw materials to build the necessary components, and were the needed minerals produced from mining companies that followed necessary safety protocols, fair labour practices and environmental sustainability procedures.

First, learners need to be aware that many of the minerals, including cobalt, used in batteries for laptops and mobile phones, coltan, also used in mobile phones, and tantalum, extracted from coltan and used in making capacitors in electronic devices, are often mined in the world’s poorest and politically unstable regions. For example, some of the largest deposits of cobalt are located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where child labourers are forced to endure dangerous working conditions, such as mine collapses and cobalt dust while working for little pay. (“Apple, Tesla Among Tech Firms Sued over DRC Cobalt Mine Abuses,” 2019). Most times mining companies in the DRC do not practice safe working conditions, may be tied to volatile or hostile groups that reap the mining benefits, and do not follow environmental practices that prevent water contamination all the while putting labourers and locals at risk. Furthermore, the minerals are often sold to and used by multi-billion-dollar companies in the building of the components for their technology devices.

Second, students should also be aware of the human labour involved in the creation of the components themselves, and how many workers endure working long hours in overcrowded factories, where they complete repetitive tasks for very little pay. Several factories in China, again many associated with multi-billion dollar tech corporations, have been accused of, and in some cases charged with their poor working conditions and treatment towards workers.

Lastly, it is also essential to provide learners with information that not all technology companies operate in both inhumane and negligent manners. In fact, some companies have made strides to ensure labour and environmental abuses do not occur; and research has occurred regarding what minerals can replace cobalt and tantalum. Ethical Consumer is a website, where companies, such as Fairphone, tracks where its minerals and components come from to ensure no human rights abuses have occurred in the creation of their phone (“Mobile Phones,” 2020).

SO WHAT:

Taking the time to discuss with my learners, unjust issues related to the creation of digital technology devices, I believe, is important to discuss the human factor related to the creation of technology. It enables learners to gain an understanding of complicated issues that can be related to items in our lives that we simply take for granted. Furthermore, it empowers learners to consider or research what steps some technology companies have completed to become or maintain their ethical practices, thus providing consumers with a choice.

A resource our Humanities Department uses, that focuses on the topic of digital or technological ethics, is the novel Blue Gold, written by Elizabeth Stuart. The book embraces the lives of three individuals, from around the world, and who are impacted by cell phone technology in very different ways. While one character, situated in North America, is struggling with the ramifications and embarrassment of her online behaviour, the other two experience more life-threatening situations. These two characters, one living in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the other in China, are impacted, respectively, by the extraction of coltan, otherwise known as blue gold or “the conflict mineral” (Fair Congo, 2019), and the labour conditions endured in the assembly of the technology devices themselves. The stories in Stuart’s novel have provided our learners with a different perspective of technology which is not often discussed. As a teaching tool, it enables learners to identify that technology is not fun and games for everyone. The book fosters discussion and encourages learners to question and research technology companies to see what policies they follow to promote ethical behaviour and practices.

NOW WHAT:

I recognize that there are no easy steps that can be taken to solve the previously discussed problems associated with the inhumane practices some technology companies are associated with. Yet, I still believe it is important to recognize and discuss these situations as they do occur. With more discussion, who knows where it could lead or lend itself to? It may encourage more companies to continue with or even start making ethical changes, it may lead to new innovations in technology that are not as dependent on rare earth minerals, thus decreasing the environmental impacts of mining, it may encourage some youth to be researchers, engineers and entrepreneurs, that develop future devices that are not dependent on minerals. Finally, it may lead to a simple discussion around the dinner table, where one just becomes more mindful.

Bibliography

Apple, Tesla Among Tech Firms Sued over DRC Cobalt Mine Abuses. (2019, December 17). Africa Times. https://africatimes.com/2019/12/17/apple-tesla-among-tech-firms-sued-over-dr-congo-cobalt-mine-abuses/

Bradsher, Keith, & Duhigg, Charles. (2012, December 26). Signs of Changes Taking Hold in Electronics Factories in China. New York Times, pp. A1, A14.

(2019, October 15). Fair Congo. https://faircongo.com

Knox, J. (2019). What Does the ‘Postdigital’ Mean for Education? Three Critical Perspectives on the Digital, with Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Postdigital Science and Education. http://ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/login?url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00045-y

Mobile Phones. (2020, January 15). Ethical Consumer. https://ethicalconsumer.org/technology/shopping-guide/mobile-phones

The Phone That Cares for People and Planet. (2019, August 27). Fairphone. https://www.fairphone.com/en/

Stewart, E. (2014). Blue Gold. Annick Press.

Wakefield, J. (2016, January 19). Device Makers Face Child Labour Claims. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-35311456

By Deirdre Houghton

MODULE #2 EDCI – 569: The WHAT, So WHAT and Now WHAT of Digital Technology in the Realm of Education (Particularly OER’s)

Photo by Hennie Stander on Unsplash

WHAT?

WHAT?

Open Education Practices (OEPs) have provided new opportunities to researchers, teachers and learners, through the increase of access. Stanford University Professor and a co-founder of Coursera, Daphne Koller stated that “…there are new opportunities that online learning opens up that would never have been possible without [digital] technology” (Brainy Quote).True. Digital technology has transformed education and learning experiences for researchers, educators and learners. Open Educational Resources (OERs), Open Digital Textbooks (ODTs) and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), as discussed in both Reflection on the Impact of the Open Education Movement, by Grainne Conole and Mark Brown, and EDCI – 569 course discussions, enable many possibilities including, but not limited to, economies of scale, increased access to knowledge and information, flexibility in learning, cheaper access to information than traditional printed textbooks, updated curriculum, further development of technology skills, opportunities to improve teaching practices, differentiated learning strategies, collaboration on a wider scale, sharing, increased scholarship for both individuals and institutions, and increasing research opportunities. In spite of the positive characteristics, and opportunities associated with OERs, ODTs and MOOCs, they are not without their challenges.

I am a firm believer and supporter that everyone has the right to an education and should have free access to knowledge, at all levels of education, including K-12 and post-secondary. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 26, section 1, states that “Everyone has the right to education….Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.” This declaration outlines not only the right to education, but its accessibility. Many post-secondary schools, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Open Courseware for example, and public schools offer a range of courses available online or in distributed format. Furthermore, there is also the development of online repositories housing e-textbooks, thus reducing the need to purchase costly textbooks. Thus, one would think, with all the technology available today, and the opportunities it has provided in the world of education, accessing knowledge and information would be relatively easy and equitable. Unfortunately, that is not always the case.

SO WHAT?

On a local or personal level, I currently work in a district that hosts an online school which provides education options for thousands of cross-enrolled students throughout BC, in addition to students in our own district (this is not to be confused with true open education). While I support the openness and flexibility that this online school and others provide, I do question the concepts of accessibility and equity, in general for all realms of education that classify themselves as truly, open. For example, students that live in very remote regions or live in families that may not be able to support or afford internet access at home, or even own a computer, gaining open educational resources, open access and e-textbooks are very difficult, if not impossible, to access. Consequently, there will be the reliance upon the traditional school setting and textbooks, and in some cases, remote learning may involve physically mailing in school work and waiting for replies, as internet connection is poor to non-existent. Further situations where access to online information for educational purposes is limited, if not impossible to access, are in countries where governments have strict control over online content, or countries meeting the classification as developing countries. Again, although I see the benefits of open educational resources, access, sharing and learning, I recognize there is a dichotomy with this style of learning because not everyone has the same opportunity or equity of access, thus reducing the ease of accessing information and knowledge.

A second area I question, regarding OERs, is the management or curreation of resources. In order for free online courses, resources and e-textbooks to maintain their accessibility, it is necessary for someone to maintain the site(s) on which they are located. I was surprised to find out that BC is one province that hosts a repository for OERs (BC OpenEd). Again, although I support this method of access to educational information, as it supports the argument that everyone has a right to education, my quandary is, how long will the site be maintained, and is it currently aligned with new curricular changes?

NOW WHAT?

With all the new technology out there, how do we ensure that education is easily accessible? How do we make sure that everyone can get, or have access to the internet to access valuable resources? These are questions that will need to be addressed in order to ensure that open resources are indeed open.

By: Deirdre Houghton

Piecing Knowledge Together: The Completed Puzzle on EDCI-515 & EDCI-568 – FINAL BLOG REFLECTION

Photo by Ryoji Iwata on Unsplash

Photo by Ryoji Iwata on Unsplash

Introduction

When I consider a puzzle, each piece’s edge enables a connection. Some pieces may not physically fit together, because of their proximity. However, the completed puzzle represents interconnections, as each piece assists in creating the complete picture. As I reflect on EDCI 515 and 568, the areas I connected with, as a teacher-researcher, and which enabled me to complete a cognitive puzzle of knowledge, include: 1.) Educators use of social media as a form of communication with students; 2.) Decolonization practices; 3.) Student inquiry learning methods; and 4). Action research through the lens of the 4Rs, and how it can assist both the teacher-researcher in developing best practices, and learners as they explore inquiry learning.

EDCI 515 & 568 Puzzle creation by D. Houghton

Educators Use of Social Media

Hearing of educators using social media, such as Twitter, to communicate with students, for educational purposes, initially, shocked me. My naivete and concern around ethics, regarding this style of communication, simply led me to believe it was wrong. However, upon reading the article by DeGroot et. al., I realize that there is a place for educators to use social media as a tool to communicate with learners. This article provides information outlining the perception of instructors’ credibility, for using Twitter as a means of communicating with college students. Arguments supported this style of communication, between instructor and students, and were seen as being beneficial for reasons, including: accessibility, information, improving instructor-student communication and relations, and student engagement. Initially, I was completely against this method of communication. However, the article brought up some valid points, and consequently, has pushed me, as the teacher-researcher, to consider creating a blog, or web-page, for my courses next year. Utilizing this method of communication with my students, will enable them to seek access to course specific material, dates, and other educational supports outside of the regular school times. Although the form of online communication I will be using is not as open as Twitter, it will provide accessibility and support to all students.

Decolonization Practices

I connected with Shauneen Pete’s class discussion and her narrative inquiry Meschachakanis, A Coyote Narrative: Decolonizing Higher Education, regarding the decolonizing of teaching methods and curriculum. I agree with Pete’s statement that “decolonization begins with naming colonial structures, then moving to re-frame, remake and reform them.” (Pete, 2018, p. 173) As a teacher-researcher, who teaches Social Studies, I feel it would be unethical, if I were to discuss and teach from only colonial perspectives, regarding the development of Canada. It is essential that students gain knowledge and understanding, of the colonization process, which led to the destruction, and dehumanization, of First Nations culture. Furthermore, I agree with Pete, that as educators, we must start making changes to curriculum and practices ourselves. It is no longer OK for educators to rely on First Nations individuals to do this teaching for us; it is our responsibility. It is time that educators take steps to, truthfully, illustrate the destruction, pain, distrust, and abuse of power, that colonial systems created, during the settlement process. It is simply not enough to invite a First Nations elder to one’s class to discuss a cultural issue, or historical wrong, and then move on. More learning and the educating of ourselves’, as teacher-researchers, must occur so we can educate our learners. As previously discussed in an earlier blog of mine, that focused on this topic, there are many ways teacher-researchers can incorporate decolonization methodologies into their teaching. Engaging students in inquiry projects that focus on Canada’s unethical treatment of our First Nations population, would enable learners to pick a specific topic that interests them, and dive deep to gain insight, knowledge, and understanding of why specific events occurred, and the horrific outcomes that resulted. By employing the research methodology of Action Research (which will be discussed later in this reflection), to complete an inquiry project, students will have the opportunity to question, gather information, reflect and continue this investigative, learning process, as they work to complete their project. Making changes to curriculum that supports decolonization, are steps that lead toward reconciliation, which are part of the Social Studies 10 curriculum outcomes.

Inquiry Process for Meaningful Learning and Personal Growth

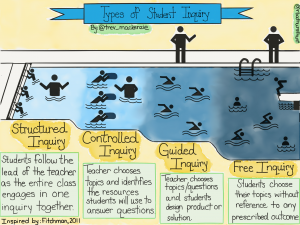

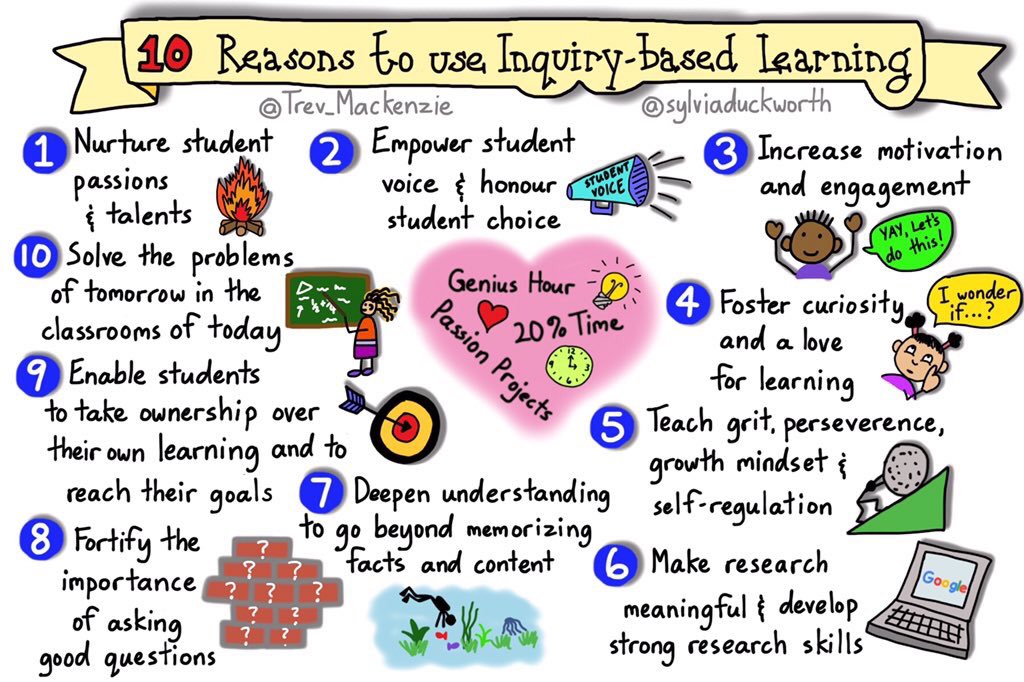

Illustration by Trever MacKenzie

Teaching for Meaningful Learning, by Dr. Brigid Barron and Dr. Linda Darling- Hammond, the Most LikelyTo Succeed, film on High Tech High, and guest speakers, author Trever MacKenzie, and Jeff Hopkins from the Pacific School of Innovation and Inquiry, shared their knowledge of different types of inquiry methods and learning styles. As a teacher-researcher, I support this method of learning, as it enables students to explore their interests, and deepen their knowledge and understanding while focusing on a particular topic. The inquiry method of learning is an exciting process to watch unfold. As a teacher-researcher, you get to witness students’ discoveries, ownership, and pride in their learning. Furthermore, the method of inquiry learning supports the fact that not all students learn the same. Inquiry learning enables learners to utilize their strengths and unique skills to complete a project. There is so much more to teaching than simply reading the textbook to students or showing a video. The proponents, of inquiry-based learning, identify that this style, or method, of learning provides students with the opportunity to engage in different activities that cultivate their knowledge. This facilitates in their understanding of a concept, an idea, and/or their ability to answer in-depth questions. Trever Mackenzie, highlights various levels of inquiry educators and students can follow depending on where students skill levels are in completing an inquiry project.

The inquiry process enables learners to be creative, and facilitates investigation and collaboration amongst peers. Learners, for example, may engage in mock debates, choose to create music, artwork, digitally created models, and or a carefully constructed showpiece to demonstrate their knowledge. The process of inquiry is a far superior learning method, compared to sitting at a desk and simply answering questions. Lastly, this method of learning fosters the development of skills needed in life, including, but not limited to: problem solving, communication (reading, writing and speaking), commitment, time management, and organization.

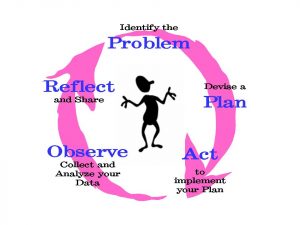

Action Research Methodology in the Classroom

Getting To Grips With Perspectives And Models, as described by Mary McAteer, connected with me as a teacher-researcher in two ways; including the further development of my teaching practices, and as a guide my students could follow while completing an inquiry learning project. In terms of my teaching practices, I could employ this methodology (as the researcher) to document and examine my students’ progress (the researched), while completing the Social Studies 10 course. Action research would enable me to reflect upon where, and how, I need to improve my lessons, thereby improving student learning (the research). Myself, as the reader of the action research reflections, would be able to see where I need to make changes to lessons, then move through the action and reflection cycle again. In terms of students using action research as a guide to complete inquiry projects, they too could employ the cyclical steps of this methodology to carry out their process of inquiry learning. In this case, the students would be the researchers, who would plan and develop their inquiry question, which would lead their inquiry research. Students gathering of information, and building of knowledge, culminating in the answer to their inquiry question, would be the researched. Readers would be the students as they reflect back on their project, and then eventually me as a teacher-researcher, as part of my assessment. Employing the action research methodology to complete an inquiry project, enables students to plan, act, make observations of their learning, reflect on their progression, and continue the cycle process until the project is complete. (Illustration of Action Research Cycle, as shown below).

Conclusion

Although EDCI 515 and 568 were focused on different areas, in terms of course layout, they both had themes that were interconnecting, and fostered further development in understanding that I can utilize as an educator in my classes this coming school year. The four areas, as reflected on above, were the main concepts that resonated with me as a teacher-researcher. These areas, although they may have been taught separately, are interconnected as they share aspects, insight and knowledge. The four areas I connected with are significant to me, because they have broadened my mind, and provided me with knowledge and skills I can bring back to my classroom, to create a learning design, with the ultimate goal being to enhance my students’ learning experience and improving my teaching practices. My new learning design will include: online communication to my students, that is accessible to all, and provide course specific information; increased learning regarding decolonizing; the employment of inquiry learning and action research steps to facilitate and support learning. Connecting the puzzle pieces from EDCI 515 and 568, have provided me with a completed picture, as to what I want to develop, professionally, to assist my students in educational growth.